Web workers with React and TypeScript

· 8 minutes of read · views| Annoy level | Time wasted | Solvable |

|---|---|---|

| 16h | Hell yeah! |

One thing that particularly bothers me when working with libraries/frameworks like React is their hidden overheads. Everything generally functions smoothly, but when you delve into less common use cases, you're likely to encounter some nasty bugs🐛.

While the reasons behind these bugs are often clear, finding a solution within the framework's constraints can be quite challenging. That's what happend to me while I was working again with web workers.

The good 🦸♂️ #

While working on my Shan Shui project, I set out to create millions of SVG paths and swiftly integrate them into the DOM. Each frame I rendered included numerous layers, ranging from 4 to around 100. Many of these layers contained thousands of SVG elements, sometimes even more. Rendering all layers simultaneously would boost rendering process significantly compared to the standard synchronous JavaScript approach.

When thinking about speed and parallel computation in JavaScript, there is only one star: web workers⭐. Their ability to work independently from the main thread and their true multi-threading capabilities caught my attention immediately.

My first draft code simply followed the MDN tutorial.

this.someArray.forEach((element) => {

const worker = new Worker("worker.ts"); // worker.ts is within same folder, da!

// ...However, this does not work in a React project because the bundler does not understand that this specific string should be replaced during compilation with the new path to the bundled JavaScript file.

After some digging, I found a clever solution that works with React's bundler.[1]

const worker = new Worker(new URL("worker.ts", import.meta.url)); Now, with the help of promises, I can render the entire scene just as I showcased in my GitHub Gist.

The bad 🦹♂️ #

Let's split the previous one-liner so I can explain what's happening here.

const url = "worker.ts"

const base = import.meta.url;

const path = new URL(url,base);

const worker = new Worker(path); // this is just the same code, yeah? Well...not in Reactbaserepresents the URL from which the script was obtained. More on import.meta.url.pathcreates a new URL object after resolving relative references betweenurlandbase.workercreates a new Worker object using a string frompath's URL object.

Everything seems straightforward, but there's a 💥ZONK💥 - it's not working!

The code fails with error: Refused to execute script from '<URL>' because its MIME type ('video/mp2t') is not executable. So now, my worker's TypeScript code appears to be treated as a video.

Important

According to webpack's doc: "(...) while the Worker API suggests that the Worker constructor would accept a string representing the URL of the script, in webpack 5 you can only use a URL instead. Using a variable in the Worker constructor is not supported by webpack".

This limitation exists because webpack needs to analyze the URL statically during the build process. This requirement ensures compatibility with native ECMAScript modules and scenarios where a bundler is not used.

We could just skip this way of passing the URL object and do it directly. However, if you ever consider (just like I did) creating a custom worker class, you might have a bad day ahead of you.

class CustomWorker extends Worker {

constructor(scriptURL: string | URL, options?: WorkerOptions) {

super(scriptURL, options); // React intensifies breathing

}

}The new CustomWorker(someURL) constructor will fail with the same issue as before.

The simplest solution is to use a one-liner for your project or a workaround where the worker's code is written in JavaScript (which does not cause a MIME type issue). If you really need to pass the URL as a variable, or build worker with TypeScript, you can use a trick that I learned while trying to fix another worker issue.

The ugly 🥸 #

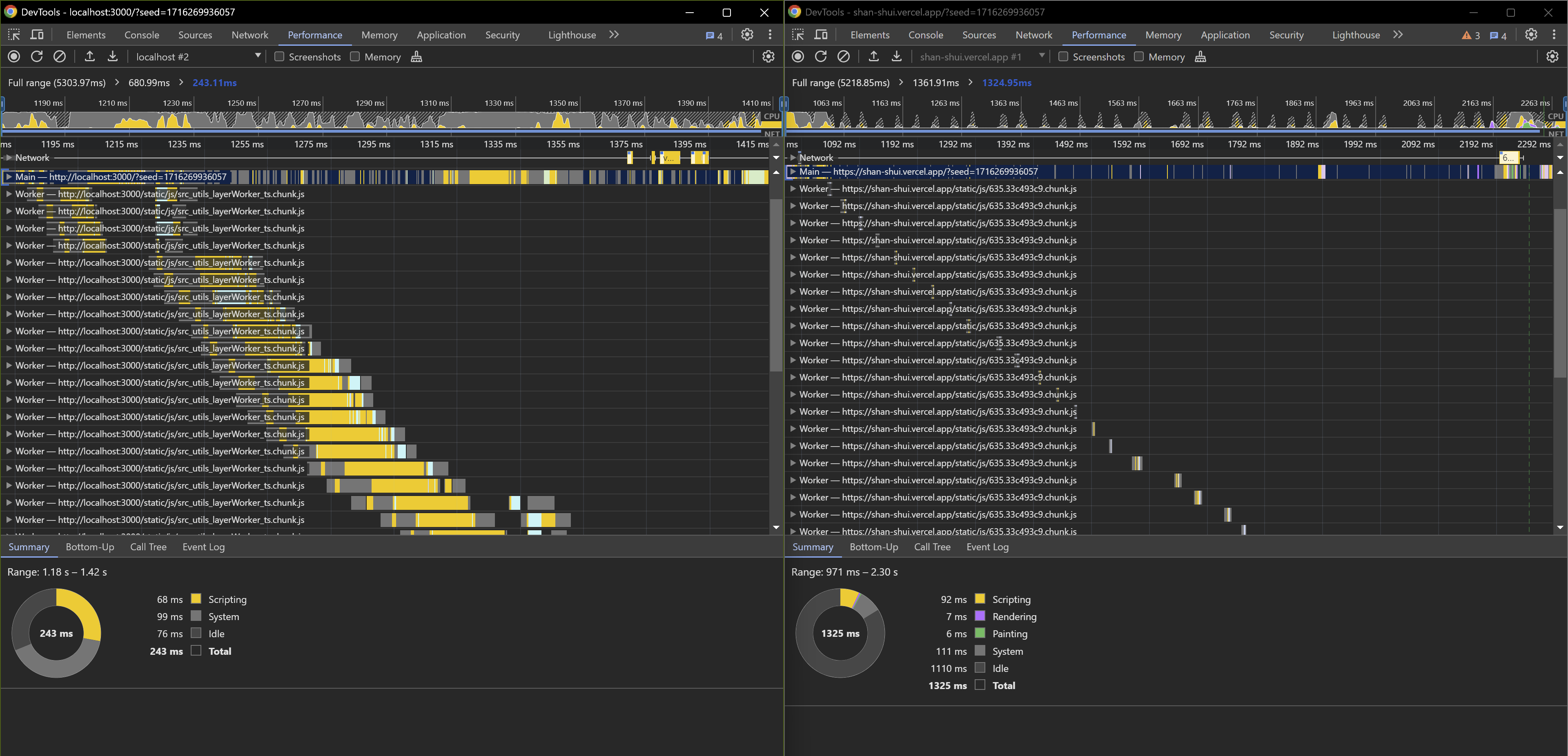

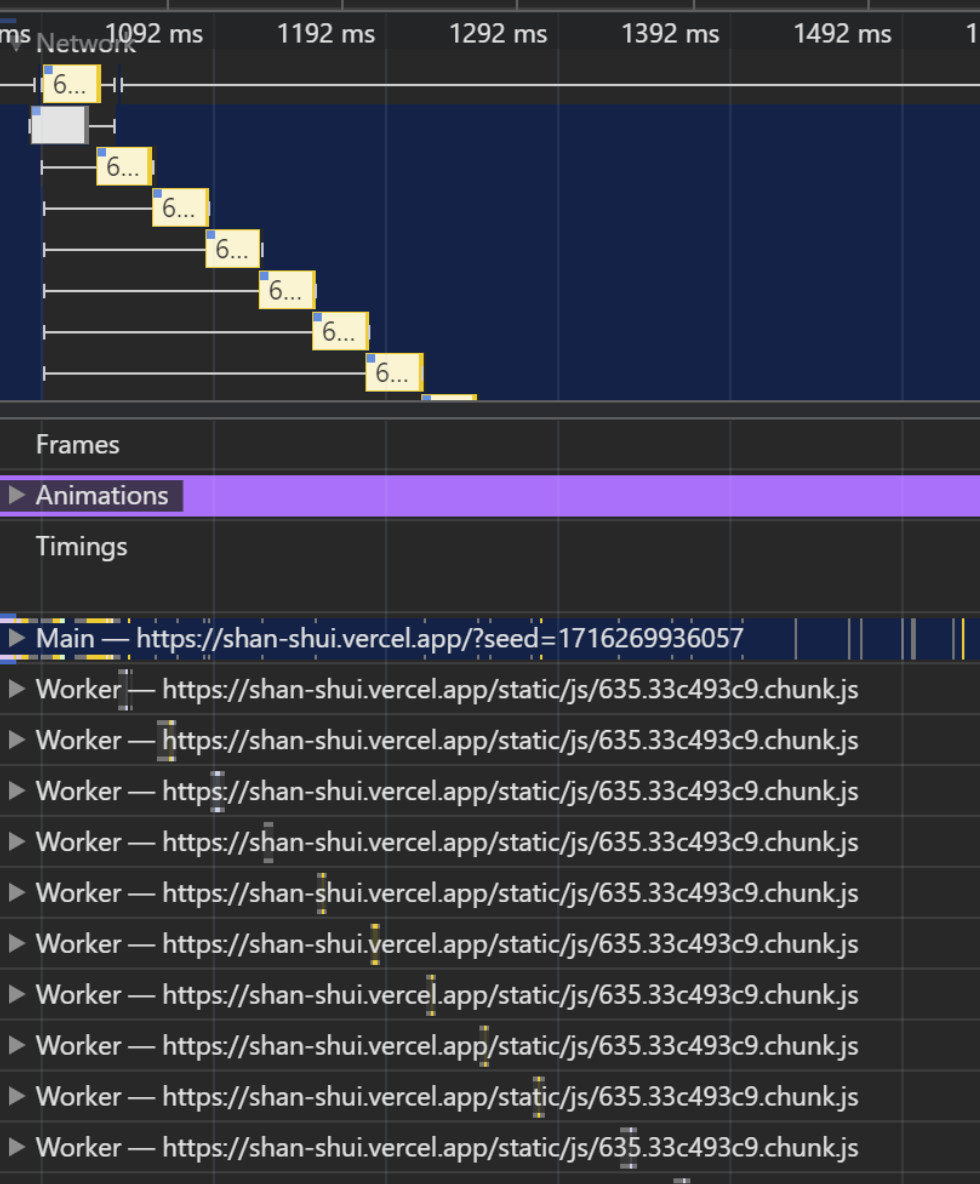

While happy about my nitro-speed worker approach, I published the project on Vercel. Then, the nightmare of every engineer occurred — it works locally (almost) perfectly, but stutters in production. A quick comparison between the two versions shows a major flaw: the workers are now working sequentially! Somehow, the parallelism disappears[2]. What took 243ms on localhost now takes 1.32s in production[3].

It was not long after I thought, "maybe the network requests are the issue here", and I was right. Unfortunately, network requests made by Workers are not cost-free.

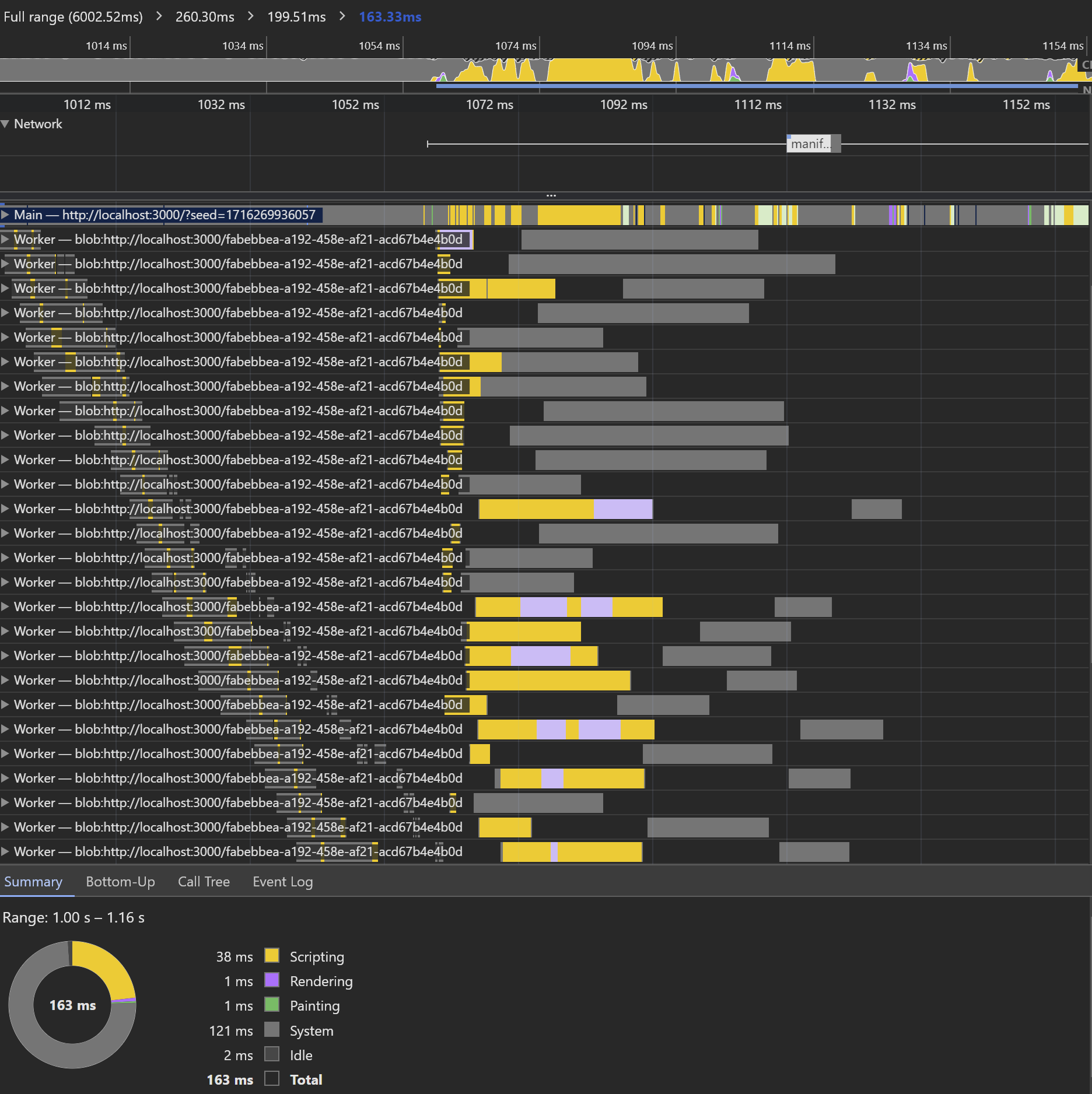

After a few more readings, I found this solution which relies on the Blob constructor. It consumes the stringified version of the main worker's function and then passes the Blob object into URL's createObjectURL static method.

// worker.ts file //

const workerFunction = function () {

onmessage = function (e: MessageEvent): void {

const element = e.data.element;

const result = element + "!" // Just as an example

postMessage({ result: result });

};

}

// Stringify the whole function, getting everything between first {} brackets,

// creating a blog containing onmessage function and URL from that Blob object

const code = workerFunction.toString()

const funBody = code.substring(code.indexOf("{") + 1,code.lastIndexOf("}"));

const blob = new Blob([funBody], { type: "text/javascript" });

const workerBlobURL = URL.createObjectURL(blob);

export default workerBlobURL;

// main file //

import workerBlobURL from "worker.ts";

this.someArray.forEach((element) => {

const worker = new Worker(workerBlobURL);

// ...I gave it a try, and it works astonishingly well. All the network overheads have vanished, and now the rendering of all the layers takes just 163ms!

Tip

When creating a worker without worrying about network request overhead, simply use a Blob and create it on the fly. The same applies to custom workers created in React - pass the Blob-generated URL object as the argument instead of a regular path.

The only downside of using Blobs is that complex objects with import statements will recreate the issue with multiple network requests. What's worse is that they will all link to a copy of the imported scripts. Therefore, when there is a need for information flow between the created elements, this solution will fail badly, creating more issues than it solves.

Further optimalization #

Workers work best when you use them in line with the number of logical processors available to run threads on the user's computer. This number can be obtained by accessing the Navigator's hardwareConcurrency property. This way, we can partition the data (for example, my array of layers) into chunks of length equal to the logical processors.

function chunkLayers(layers: Layer[], size?: number): Array<Array<Layer>> {

const chunkSize = size || navigator.hardwareConcurrency;

const result = [];

for (let i = 0; i < layers.length; i += chunkSize) {

result.push(layers.slice(i, i + chunkSize));

}

return result;

}...and then create pool of workers that will process each piece in the fastest possible way.

const chunks = chunkLayers(this.layers);

const framePromises = chunks.map((layers) => {

const chunkPromises = layers.map((layer) => {

return new Promise<string>((resolve, reject) => {

const worker = new Worker(workerBlobURL);

// skipped worker's onmessage, onerror, postMessage

});

});

return Promise.all(chunkPromises);

});

return await Promise.all(framePromises);In my code, this approach doesn't bring any speedup as the data is not that complex, and I need to wait for all the promises to be resolved. In the tested example, only around 50k elements were rendered, which brings the total time per element to around 4μs. Further improvement could be limited by the overhead associated with using Promises. However, for more complex processes where data chunks are not related to each other, it might be the go-to option.

Making it work in TypeScript and the WebPack bundler (without React) is another level of flexing ↩︎

Only when publishing this post did I notice that the local version was suffering from the same issue, but to a lesser extent, as there is much less network overhead on localhost ↩︎

I tested all the performance benchmarks on the same picture ↩︎